in a Changing World:

Trade, Currencies

and Capital Markets

Global Head of Research, EXANTE

as feared

In October 2025, the WTO revised its forecast for global merchandise trade growth for 2025 to 2.4%, up from 0.9%, while trimming its 2026 projection from 1.8% to 0.5%. The International Monetary fund (IMF) now expects global growth of 3.2% in 2025

and 3.1% in 2026.

The IMF notes both growth and corporate agility have proven more resilient than expected under President Trump’s tariff regime. In its October World Economic Outlook it credited new trade deals, front-loaded imports and re-routed supply chains with cushioning the impact of the tariffs.

Yet for all the talk of resilience, the real story may be one of accumulation, of tariffs, debt, and fiscal pressure now beginning to unsettle markets.

The federal government logged a $1.8 trillion budget deficit for the 2025 fiscal year, little changed from 2024, despite a surge in tariff revenues under President Donald Trump’s trade war. In September alone, tariffs brought in more than $31 billion, with receipts apparentlytopping $215 billion year-to-date according to the US Treasury.

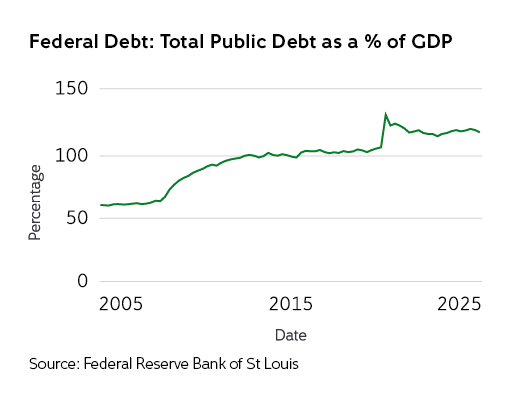

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO),estimates that the shortfall for the fiscal year ended 30 September was only $8 billion less than 2024. Yet the “big, beautiful tax and spending bill” pushed through earlier this year has sharply altered the outlook. The US national debt now exceeds $37.4 trillion, around 120% of GDP, and is projected to pass $40 trillion within months.

Servicing that debt is increasingly expensive. The Petersen Institute for International Economics, expects interest rate payments for the 2025 fiscal year to reach $933 billion, well above 2024’s cumulative payment of $843 billion. It is the fastest growing line item in the federal budget.

The CBO projects that, under current law, net interest payments will hit $13.8 trillion over the next decade, rising from an annual cost of $1 trillion in 2026 to $1.8 trillion in 2035. On present trends, debt could rise to 166% of GDP by 2054.

Meanwhile, that “big beautiful bill” is already eroding corporate receipts. Income-tax revenues fell 15% year-on-year as firms claimedlarger deductions for certain investments in 2025. And although a federal appeals court has ruled many of President Trump’s tariffs illegal, the decision has been stayed pending Supreme Court review, leaving the White House free, for now, to widen its tariff net still further.

The euro area is the world’s biggest external holder

of US debt securities and owns a significant share of US equities. A slowdown in the United States, therefore, threatens Europe on two fronts: Bond markets and trade balances.

According to data from the European Central Bank (ECB) and Saltmarsh Economics, the euro area’s current account deficit with the US reached €20bn in the first half of 2025, almost matching the total for 2023 as a whole. Although Europe still runs a substantial goods surplus with the US — around €137bn over the same period — this is offset by a widening deficit in services, which reached €93 billion. Over the 12 months to the first quarter of 2025, the goods surplus rose to €254 billion, but the services deficit deepened to €172 billion.

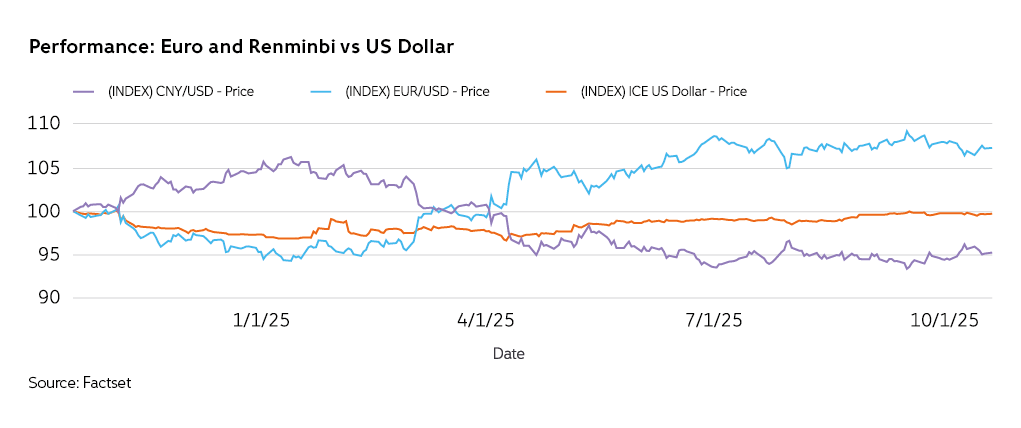

Currency movements compound the problem. Despite the ECB cutting interest rates, the euro has strengthened roughly +12.5% against the dollar year-to-date. A persistently strong euro risks making European products too expensive for the US market, still one of the region’s biggest customers. A weaker US dollar meanwhile reduces American purchasing power abroad, potentially eroding demand for European goods and widening Europe’s overall current account deficit with the US.

The macro implications are clear: lower export earnings could weigh on growth, hiring and investment in the eurozone, particularly in export-heavy economies such as Germany and the Netherlands. Europe’s reliance on US demand has long been a strength. Now it may prove a vulnerability.

US dollar down, but not out

The US dollar has lost some of its shine, but not its standing. It has fallen just over 9% so far this year, after suffering its worst first half since 1973. According to Morningstar research, the DXY index — which tracks the greenback against major trading partners — fell 11% from January to June, ending a decade-long rally that began in 2010 and delivered nearly 40% cumulative gains.

The shift reflects more than market rotation. Changes in US trade policy and geopolitical alignments under the second Trump administration, coupled with improving economic sentiment in Europe, have led some to declare the end of US exceptionalism and the start of a terminal decline for the dollar decline. That call looks premature. The US dollar remains the backbone of the global financial system, accounting for roughly 58% of foreign-exchange reserves worldwide, according to the Atlantic Council. The euro, its nearest rival, accounts for 20%.

There is no substitute for the dollar

Despite various calls from the BRICS bloc to de-dollarise trade, and efforts by central banks to launch digital currencies, the plumbing of global finance remains firmly dollar-centric. Around 54% of export invoicing and 88% of foreign-exchange transactions are denominated in US dollars. Neither the euro nor the renminbi is ready to dislodge it as the premier reserve currency and perceived global safe haven.

The euro’s appeal is limited by Europe’s fragmented capital markets and scant joint debt issuance. The renminbi’s prospects are weaker still: China’s currency is not fully convertible and the risk of direct state intervention undermines investor trust.

The US dollar will remain entrenched as the world’s reserve currency for the foreseeable future. Foreign investors currently hold roughly $7 trillion in Treasuries (about 25% of the market) anchoring global confidence in US debt. Yet that confidence is not unshakeable. Slower growth and mounting fiscal concerns could dull the appeal of US assets, weakening portfolio inflows or even prompting outflows.

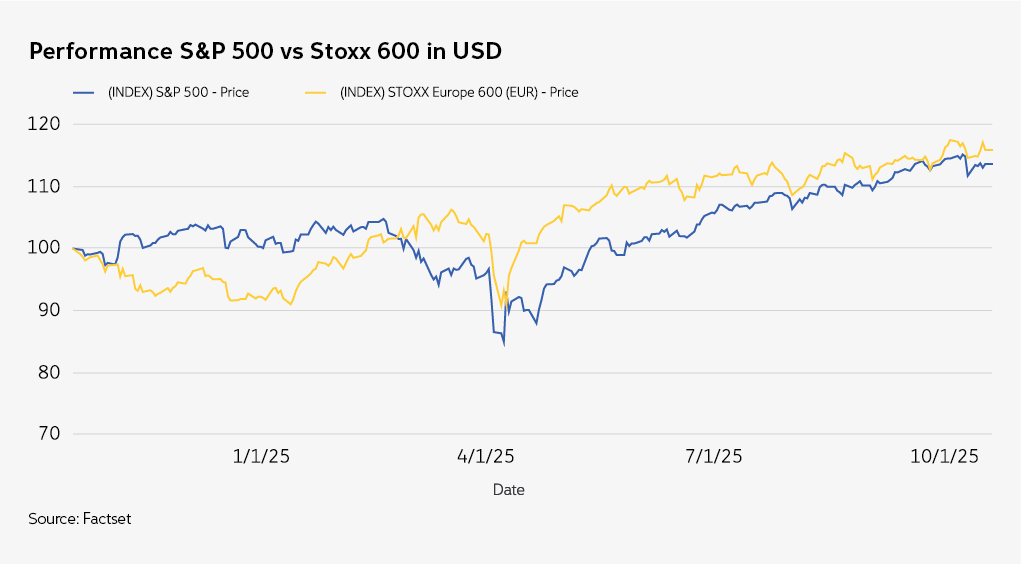

A prime example of this is Germany’s fiscal shift and the wider EU defence push, breaking from years of restraint. Expected fiscal expansion in Germany alone makes a number of sectors in Europe far more attractive to investors. Cheap valuations have helped too.

As noted by Janus Henderson Investors, the STOXX 600 Index returned 24.4% in the first half of the year in US dollar terms, significantly above the S&P 500 Index’s gain of just 6.2%. Year-to-date, the Stoxx 600 is up roughly 12%, while the S&P 500 has risen a little over 13%. With the ECB expected to deliver one more rate cut by mid-2026, European equities could enjoy further relief.

The valuation gap has narrowed, but risks persist. Uncertainty around US trade policies, new tariffs and their impact on corporate margins still hang over the euro area’s outlook.

More fundamentally, Europe remains underinvested in the technologies that are driving US and Chinese growth. French economist and Nobel Prize winner Philippe Aghion issued a stark warning to Europe on France 2’s evening news on 13 October, saying that: “Europe needs to wake up. We’re falling behind technologically compared to the United States and now China. Since the 1990s, they’ve been developing breakthroughs, hi-tech innovations, while we’ve remained confined to incremental, mid-tech innovation.”

He’s not wrong. Even with new spending in defence and infrastructure, Europe’s deeper problems endure: political discord between East and West, uneven productivity and a risk-averse corporate culture. These structural drags could prevent European stocks from realising their full potential, no matter how wide the fiscal tap opens.

At the end of Q3, the US stock market was trading at a 3% premium, a level reached only 15% of the time since 2010, according to Morningstar Research, Nearly 40% of total market capitalisation is now concentrated in just 10 mega-cap firms, most of them tied to the artificial intelligence boom and expectations of monetary easing.

But behind the headlines lurks a less comforting macro picture, one of inflationary pressures, slowing growth and stretched valuations. With the S&P 500 currently trading at around 23X forward earnings, talk of an AI bubble is getting louder, along with the prospect that it may, as all bubbles do, burst. However, for the rest of 2025 and most probably into 2026, investors appear content to stay on the AI-train, convinced it will open multiple new multi-trillion dollar markets.

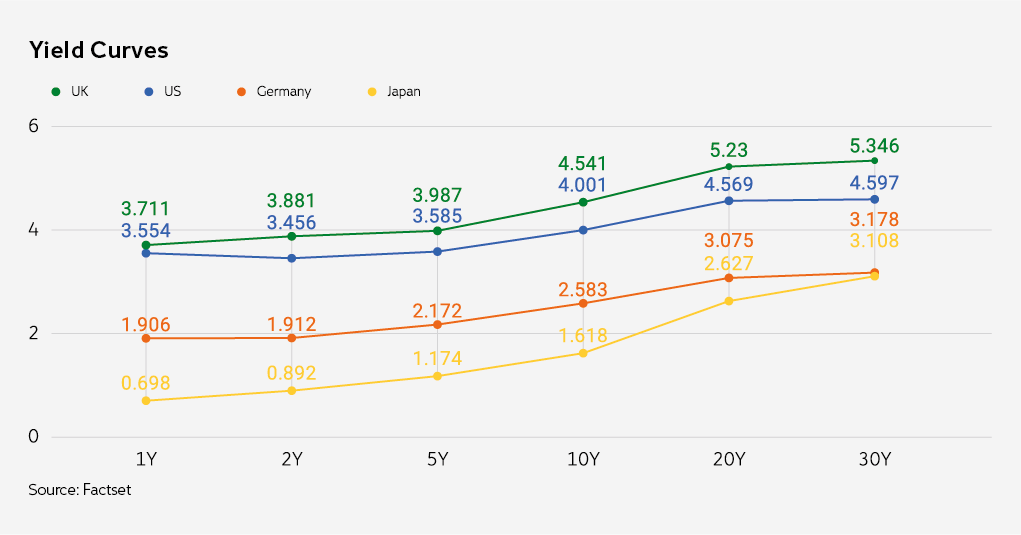

Fixed income tells a different story. As noted by Ben Lord at M&G, the steepening of yield curves we have seen this year owes less to rising inflation expectations than it does to fiscal risks and heavier issuance. In the US, tariffs have yet to feed fully into higher prices, but investors are questioning the disinflation narrative.

Goods inflation has been climbing as tariff effects filter through. According to a Goldman Sachs report dated 12 October, American consumers will bear 55% of tariff costs by year-end, while corporates absorb another 22%. And that estimate excludes the latest tariffs on China. Were those included, the consumer burden could be 70%.

Even if the Fed continues easing, as Chair Jerome Powell hinted in his speech on 13 October, bonds are unlikely to find sustained support. Concerns over debt levels and fiscal sustainability are now the dominant yield drivers.

For Europe the consequences are mixed. High US yields limit how far European yields can fall, despite ECB action offering some relief to credit markets. The United States, with it scale and market depth, can shoulder higher debt for longer. Europe cannot. Bound by stricter agreements, such as the Stability and Growth Pact, it lacks the fiscal flexibility to borrow heavily for productivity-enhancing tools. The result: slower growth potential and another reminder that in capital markets, as in policy, America and Europe still play by different rules.

As the IMF warned in its October 2025 World Economic Outlook, further escalation of protectionist measures, including non-tariff barriers, could suppress investment, disrupt supply chains, and stifle productivity growth. Larger-than-expected shocks to labour supply, particularly from restrictive immigration policies, could reduce growth and risk deepening skill shortages, especially in ageing economies such as Europe. Fiscal vulnerabilities may raise borrowing costs and heighten rollover risks for sovereigns. In capital markets, a sharp repricing of tech stocks, triggered if AI-earnings disappoint, could mark an end to the AI investment bubble with more of a boom than a pop.

Rising long-term debt will test central banks, particularly the UK and US. Yet it is not all doom and gloom. Most major central banks, Japan aside, are likely to keep cutting rates, boosting liquidity and propping up risk assets worldwide.

As ever, investors need to stay disciplined: maintain diversified portfolios across asset, currency and sector exposures; balance risk with defensives; and keep an eye on where genuine productivity gains, particularly from AI, translate into lasting value. In a world of shifting alliances and persistent tariffs, agility will be the most valuable asset of all.

While every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of this information, EXT Ltd. (hereafter known as “EXANTE”) cannot accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any person on this publication or any of the information, opinions, or conclusions contained in this publication. The findings and views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of EXANTE. Any action taken upon the information contained in this publication is strictly at your own risk. EXANTE will not be liable for any loss or damage in connection with this publication.